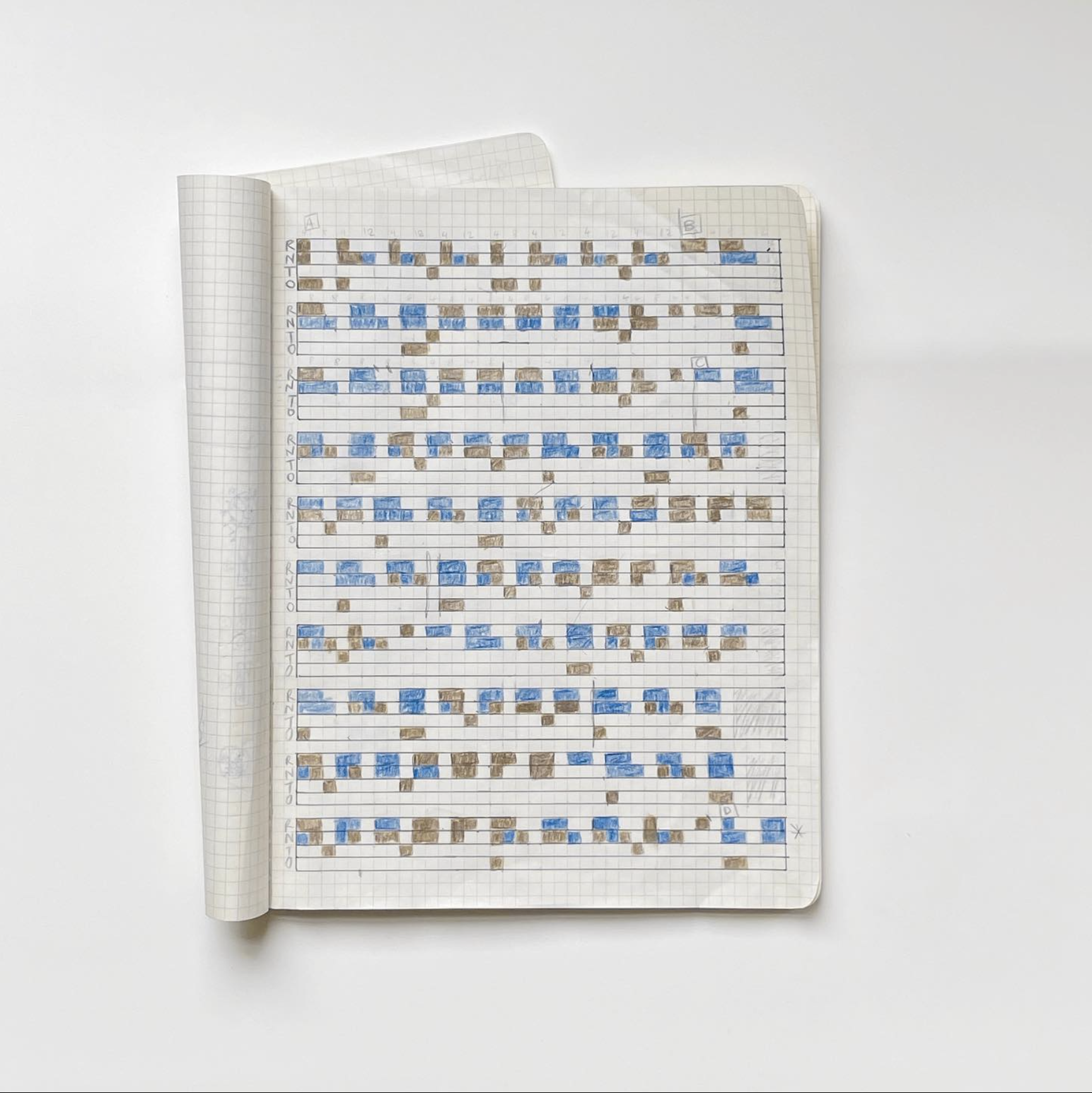

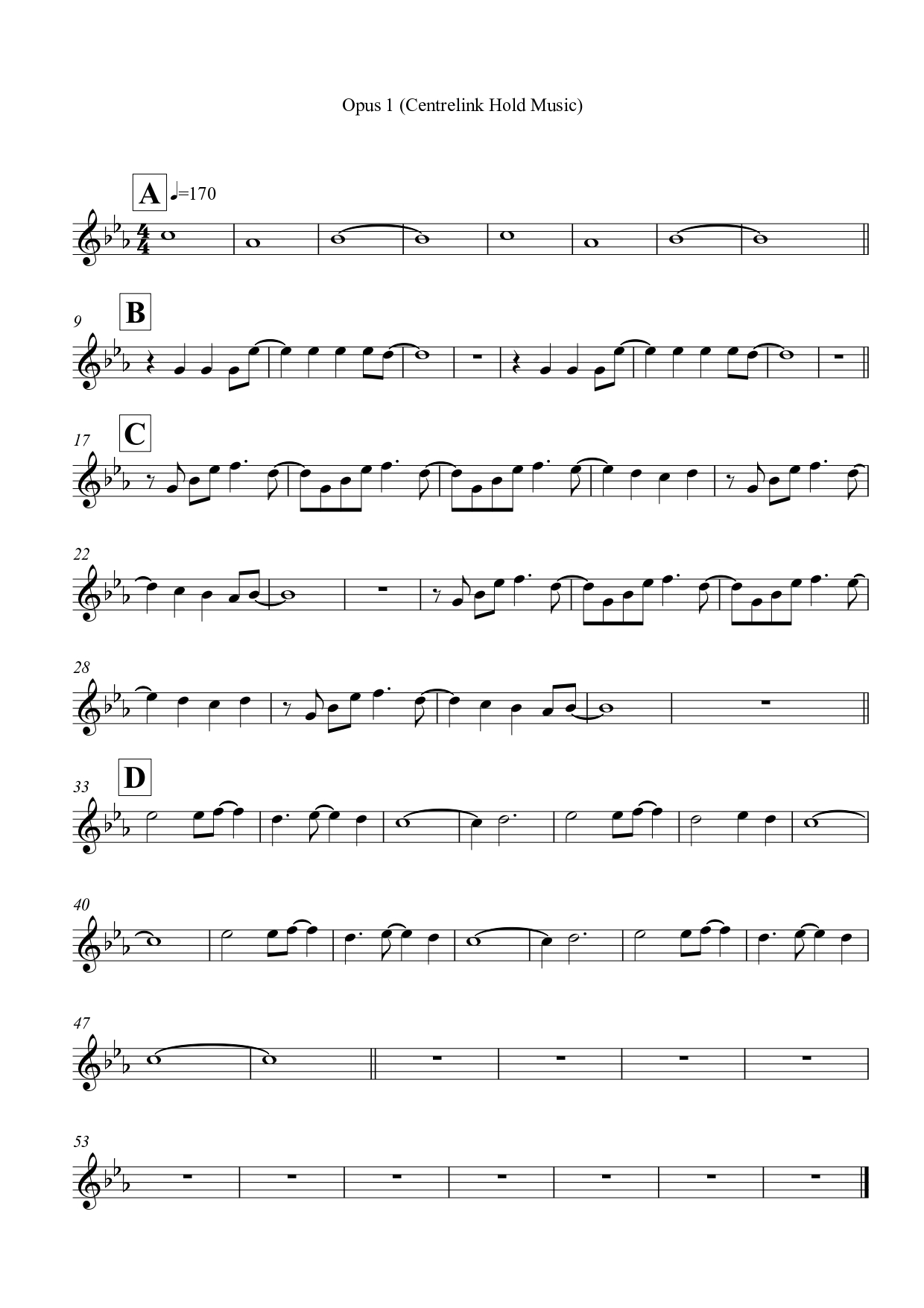

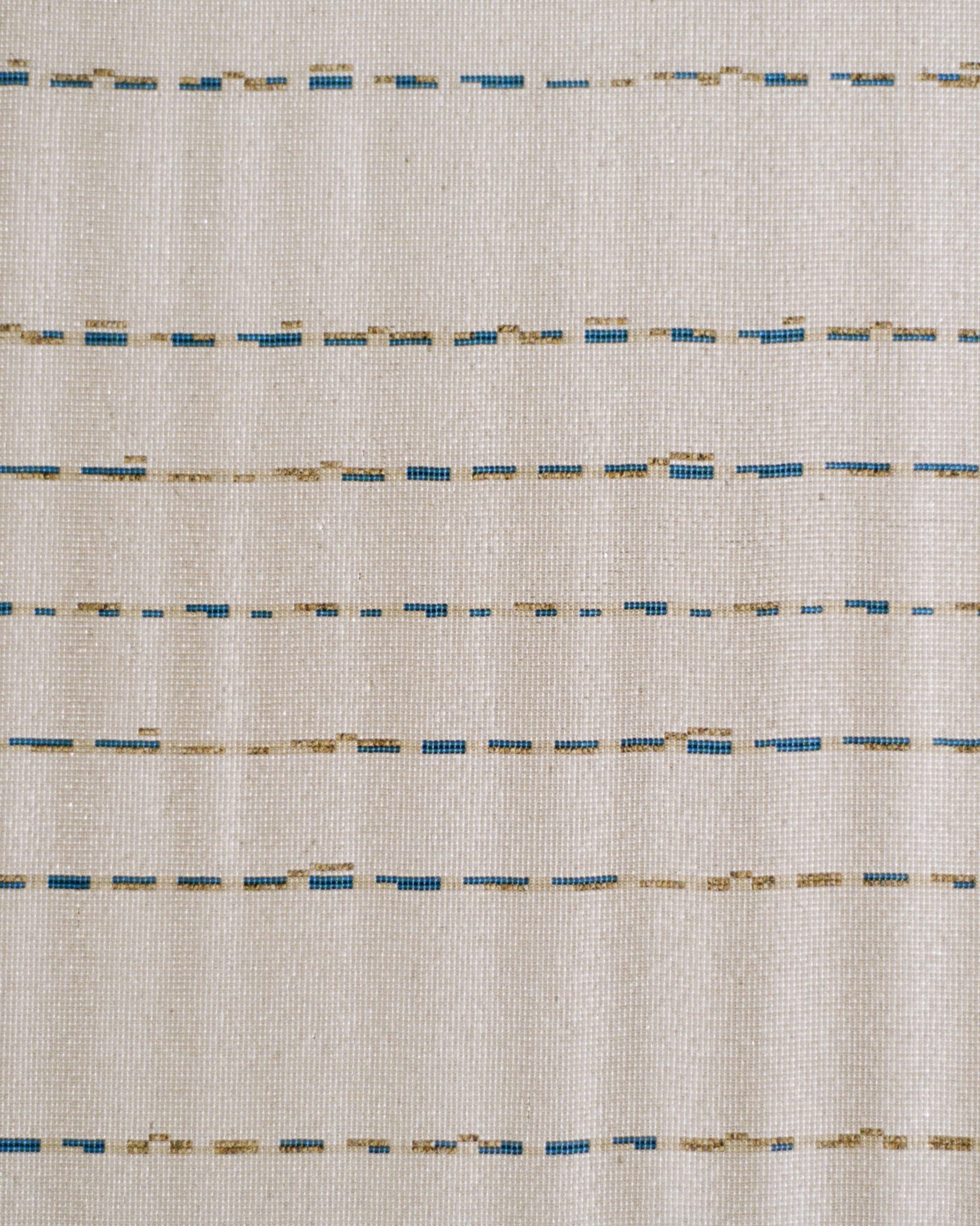

“By virtue of the grid”, Kraus argues, “the given work of art is presented as a mere fragment, a tiny piece arbitrarily cropped from an infinitely larger fabric. Thus the grid operates from the work of art outward, compelling our acknowledgement of a world beyond the frame”. Laddawan’s decision to exhibit the work on the loom attests to a sense of perpetuity or incompleteness. This feeling is further articulated through the modularity and repetition of the beaded score that follows the continual looping of Carleton’s music. Like the experience of being placed on hold, there is a niggling sense that this could continue for the foreseeable future. However with Opus 1 Laddawan puts forward a slither of this perpetuity: 120 hours of clock time or la durée marked bead by bead. Opus 1 draws attention to time spent, whether it is beading, or writing or placed on hold, it marks the accumulation and duration of ‘one thing after another’. At the same time, it attends to the world beyond the frame, the messy time of feelings and subjectivity that endures.