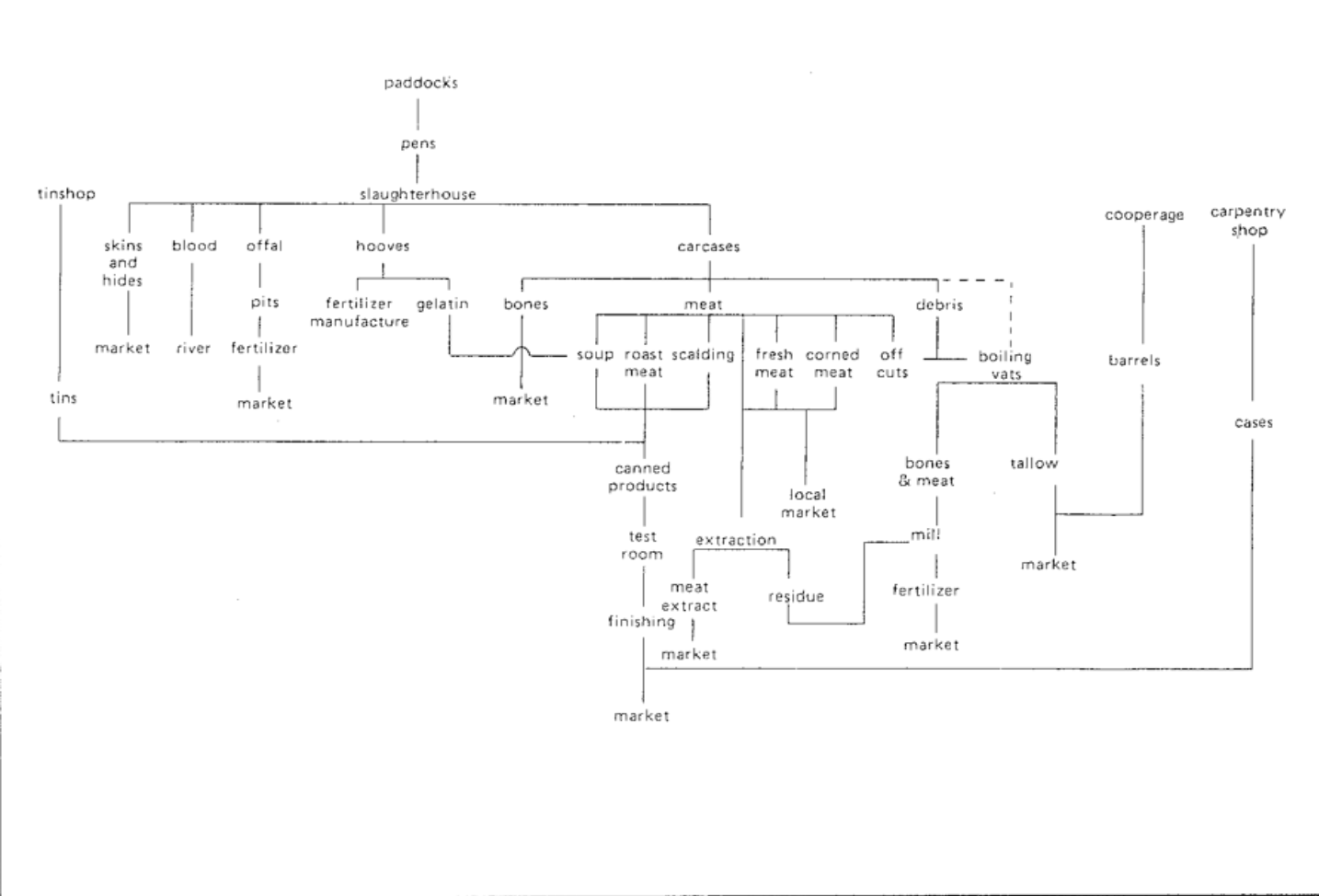

This flow chart – sourced from the archives of the Living Museum – illustrates the production processes undergone by thousands of sheep and cattle at the Australian Meat Preserving Co. Works., which opened on this site in the 1860s.1 The chart shows the journey of the animals as they passed through the company, from life in the paddocks, their death and the incremental partitioning of their bodies. In the flow chart, every part of the sheep is accounted for, laid bare for us to see. With the exception of the blood (most lost in the slaughtering process anyway) almost every part had a use, from the skin and hides, offal, hooves and the meat of the carcasses. All end up at the marketplace. Together, the skeletal forms of the flow chart might be read as the stripped ribcage, flesh and bones of the sheep themselves, fixed before a taxonomic logic aimed at extracting value from everything it looks at. The chart maps and interprets organically-occurring lifeforms, naming and categorising them to enable their ownership and subsequent commodification. It demonstrates the ways that capital is predicated on legibility, this legibility intrinsically entwined with death and ways of being that are antithetical to living.

‘Individuation’ is the act of putting legal and material boundaries around phenomena so that they can be bought and sold.2 The site of the Living Museum on unceded Boon Wurrung and Wurundjeri Country is an example of this. Seized from traditional owners to be understood within the Western legal system as Crown Land, in 1848 it was sold into private ownership, to be subdivided, bought and sold as such until the latter stages of the 20th Century. As a site of ‘exceptional significance in the industrial history of Australia’, the influence of this process of individuation cannot be overstated within a place whose trajectory was driven explicitly by colonial notions of domination, innovation, progress and profit.3 In this time, as property, its complex, ever-changing nature and the biodiverse webs of life it sustains were atomised into discrete units of information to be used, traded and broken down into smaller parts. Intricate relations of interdependendency have been recorded on this site as means by which to control them, resulting in the commodification of the natural landscape itself and the biodiverse life it supports. As Virginia Barratt notes, ‘Breath flows through the lungs of capital.’4

In 1984, in a global trend that sees many recently-established cultural institutions inhabit former industrial sites, ‘Melbourne’s Living Museum of the West’ was established in and around the ruins of industry here. Our program must consider specifically the kinds of labour produced here since colonisation in the pursuit of progress, by and for who, and how this has changed in order to suit the evolution of technology and industry in the 21st Century. From the physical labour involved in shaping and forming material goods (meat production and preservation, munitions, then concrete pipes) undertaken by the settler, migrant working class here in the Modern era, to the production of knowledge and information (essays, art exhibitions and other discursive programs) by tertiary-educated arts workers and artists today, both kinds of labour are sustained by an extractive gaze, predicated on the logics of legibility.

The national narrative of ‘Australia’ has been shaped by unique histories of documentation, identification, surveillance and control, whether that be of First Nations people and their lands, of migrant communities and individuals looking to make new lives here, or of those with different experiences of gender and sexuality. The global colonial project employs methods of naming and categorisation as forms of ownership. Under the branches of science and anthropology, then in the interests of national security, nothing here has been allowed to remain hidden from imperial authorities. For those in the arts then, what is the violence of being rendered legible as an historically marginalised person in the dominant structure of culture sustaining ‘Australia’ that gives artists and the things they produce meaning here? How are the values and modes of engagement that shape colonial histories on this continent reproduced in spaces where art and culture occur? And if we were to leave these spaces altogether, how might we find each other in the dark?

As the photograph fabricates one’s consent to be seen, so too do forums of exhibition and presentation. In these contexts, artists must decide what they wish to share with institutions and their audiences. Under harsh lights, in gallery spaces clinically devoid of all extraneous information, their artworks are viewed forensically as evidence by which to corroborate the hypothesis of an exhibition, of one’s identity and true subjectivity, or in recent times, the moral integrity of an institution. This forensic way of seeing cultural production is reinforced in the conventions of exhibition documentation and its importance within image economies, wherein the majority of people come to know a show, an artist and their work without having any direct experience of them. Because the vast complexities of life can’t be adequately held in these forums, an artwork provides a stable and fixed alternative to human ambiguity. Furthermore, in the context of an art exhibition, the complexities that an artwork represents and its value depend on the authority of an expert to speak on its behalf. Even when artists consent to performing the (often painful) role of translator, legible as evidence in this way, artworks and their makers can only satisfy audience expectations for an objective, singular and unchanging truth, that negates the inherent contradictions and nuances embedded in living and thinking creatively.

What value does evidence have in so-called ‘Australia’? Even when hard photographic and video evidence is presented in the forum of court, no police or prison officer has ever been convicted of murder for the death of a First Nations person, despite over 500 First Nations people dying in custody since the Royal Commission.5 It would seem that everywhere in this nascent colony, that only particular forms of evidence are recognised and sanctioned along lines of race, gender and class. With this in mind, what then is our relationship to truth as it is produced in museums, archives and places of learning? Why do we place so much trust in a certain practice of looking and knowing in the arts when it has been so pivotal to a worldview grounded in ambitions of control and domination? What methods might we employ in forums of presentation to remain opaque, to resist the conditions of visibility that allow cultural production to be read objectively as evidence, reinforcing rather than challenging the hunches of those with authority?

If you go to Pipemaker’s Park and close your eyes, over time you will notice the presence of hundreds of different species of animal. A dozen types of camouflaged frog that can be heard but not seen. The Eastern Bluetongue, who has the ability to self-amputate when threatened, leaving a body-double in the wake of its escape. Or the short-finned eel, which along its migratory journey turns transparent, invisible to those who seek it out in the murky currents of the Maribyrnong River. The Elmid Beetle is millimeters in length. Living in the cracks of submerged wood or rock, it eats decaying algae. Despite living underwater it cannot swim, and so crawls, semi-blind through the dark. Perhaps it might be most instructive to think about where strategies of evasion and refusal might already exist here. Diverse forms of life existing beyond the capacities of the most creative minds to imagine them, that refuse capture in the multifarious nature of their being. These things ensure a degree of privacy from the hard, extractive gaze through change and mutation, artifice, by presenting multiple versions of themselves, by hiding, by clustering together at the edges of the frame.

At least one hundred species of bird inhabit this area at different times of the year, each with their own distinctive call, pitched at a unique frequency so as to be detectable only by family through the throng of the sonic spectrum. Soundscape ecologist Bernie Krause describes an experience of listening to the weave of creature voices not only as a choir, but as a cohesive sonic event:

No longer a cacophony, it became a partitioned collection of vocal organisms – a highly orchestrated acoustic arrangement of insects, spotted hyenas, eagle-owls, African wood-owls, elephants, tree hyrax, distant lions, and several knots of tree frogs and toads. Every distant voice seemed to fit within its own acoustic bandwidth – each one so carefully placed that it reminded me of Mozart’s elegantly structured Symphony no. 41 in C Major, K. 551.6

Over time, through surprising moments of coincidence and happenstance, the format of a chorus has come to figuratively embody my feelings about a collective space in which to test our ideas.7 A space in which unnamed individuals can gather collectively to improvise, tell important truths, and in which to exist harmoniously and melodically as part of a larger whole. Engaging with a chorus doesn’t require one to look beyond the moment of performance, and entails an appreciation of timing, rhythm and tone, crucial in the task of translating sound into music. With the appreciation of sound also comes the honouring of silence. The liveness of a chorus is important to me precisely because it is alive, existing beyond frozen categories of easy classification. Indeed, the title of this exhibition hints at a mode of engagement that resists the urge to know. The great difficulty within this project is navigating the balance between preserving the right of artists to remain opaque and preserving the access that audiences need to engage with ideas. Perhaps the key to navigating this is the understanding that many of the policies of access and their interpretations we have in institutions today are themselves designed to engender a homogenous experience that enshrines extractive modes of engagement. In mainstream discourse, much more can be spoken about regarding access, and how a deeper practice of it can figure into new formulations of audience engagement altogether.8

I keep getting caught up in the idea that ‘to listen’ to someone implies a generosity of attention. Some of the works in this show are grounded in listening, while others launch off from the idea of choral harmony. Other works and their authors reference the history of this site, reference each other so – as Trinh T. Minh Ha writes – to make them sing.