“We want to bring knowledge of the past to the present, to preserve it for future generations and to understand what meaning it has in the present day and age.” [1]

– Dr. Marika, Inaugural Cultural Director of The Mulka Project

“The name ‘Mulka’ means a sacred but public ceremony, and ‘to hold or protect’. That is why we call it The Mulka Project. It is public, like a library, but not just for old things. It is also about capturing what is happening in the community today. So Mulka is always growing. It is about upgrading the vision and recording style. That is why we continue recording people.” [2]

– Wukuṉ Waṉambi with Henry Skerritt (2015)

Thank you to Joseph Brady for feedback on this essay

Founded in 2007, The Mulka Project is a “production house, recording studio, digital learning centre and cultural archive” that is “managed by Yolŋu law and governance.”[3] The Project manages an archive that actively seeks out and collates Yolŋu cultural material from institutions around the world, creates new cultural resources, and facilitates access to and creative engagement with them. It is led by a team of artists and practitioners who mentor other artists, and who both make their own work and contribute to different collective projects. A journal article on the history and concept of The Mulka Project by founding Cultural Director Wukuṉ Waṉambi and Creative Director Ishmael Marika traces the story of the archives now held by Mulka from the first visits by anthropologists to North-East Arnhem Land “recording the sounds and images of our communities since the 1920s”, and the processes of gathering thousands of recordings held around the world being led by artists (Mulka was founded from the proceeds of the acquisition by the Australian National Maritime Museum of the Saltwater Yirrkala Bark Paintings of Sea Country by forty-seven contributing artists).[4]

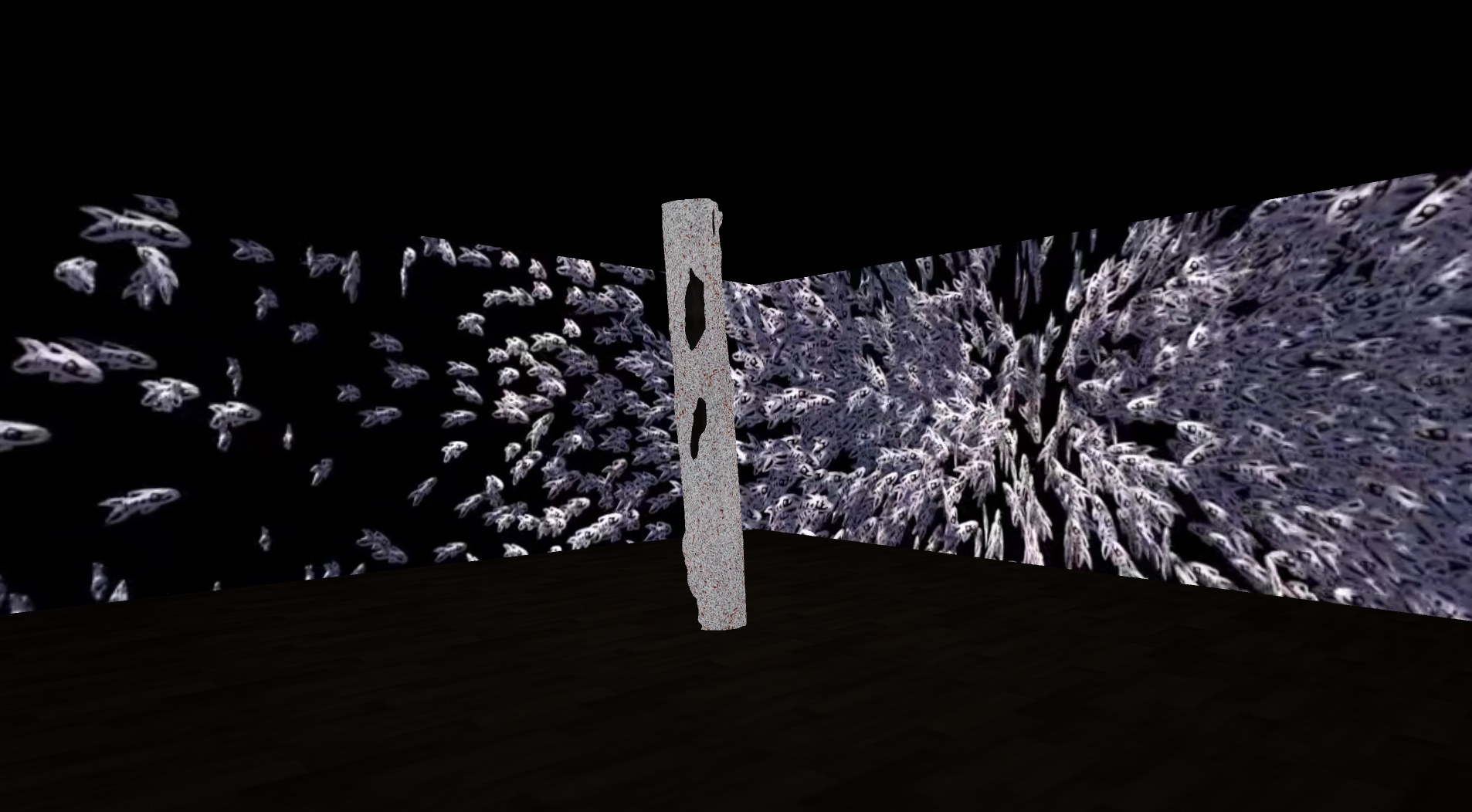

I was asked by Maya Hodge, Jenna Warwick, and West Space to undertake a piece of writing about The Mulka Project, whose work I began to get to know when I worked on the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, NIRIN, where they exhibited the ground-breaking collective filmic cycle Watami Manikay (Song of the Winds) (2020) at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (view “an immersive online rendition” of the work here).[5] When I began trying to work on this piece – beginning with the idea that I’d pitch a possible angle to The Mulka Project for feedback, I found it impossible to settle on any one idea. To begin from the discipline of art history is often to select the most suitable theoretical frame that can be applied to a particular artist or artistic movement. Maybe that’s never a particularly great way to start, and maybe also some collectives, quasi-institutions, or projects, elicit so many tendrils of activity that they always slip away from attempts at more singular framings. I don’t mean this in the way that some contemporary art projects can become so complex they become opaque, but in the way that some of the most innovative projects and collectives can simultaneously capture broad public imagination, support the vision of individual creators, and function as collectives that are constantly moving and reassembling in different formations, strengthening everyone who is a part of them, even for a short time.

This is all true in the case of The Mulka Project as a form of collective endeavour, whose grounding in Yolŋu thinking, and tethering to the transgenerational knowledge and wider relationships of every member, undergirds the powerful content they put out into the world. Their many tributaries – from functioning as a living archive, to artistic outputs, to acting as a training centre and production house – frequently re-calibrates the other institutions and people they exchange with (museums, galleries, archives, curators, researchers, film and television organisations and so on) back towards the centrality of where they come from, where they make work from, and the spectrum of relationships these practices entail. The Mulka Project are in lineage with and part of a deep cultural arena of Yolŋu artists and leaders (whose histories, stories, and artistic works are also part of the ever-growing Mulka archive) that have taught and are teaching a massive number of cultural producers and researchers across Australia and beyond Yolŋu ways of approaching things, and directing and re-directing various institutions in more Indigenous-led directions.

As I started this essay, Mulka had just released NFTs, with inaugural editions by Ishmael Marika and Wukuṉ Waṉambi, with portions of the sales of Waṉambi’s work going towards purchasing and permanently accessioning his bark painting depicting ceremonial waters in his ancestral homeland of Gurka’wuy (3-D scanned and separated into segments to create the NFTs) to the Yirrkala Museum – thus simultaneously intervening across the entangled worlds of digital artworks, art markets, collecting practices, archives and museums to ensure long-term local access to his own work.[6] As Mulka artworks flow out across the ziplines of a speedy digitised and globalised cultural sphere, artists have visions towards the long futures of their homes and homelands.

To capture then, some of the many ways that The Mulka Project operates, this essay concludes with an annotated reading list selecting just some of the many materials that Mulka has somehow contributed to or set in motion through their prolific activities, or which could be read alongside their work.